Do you have questions?

Need additional advice? No problem! Ask our team of experts. We'd love to hear from you.

Intermittent fasting (IF) has become increasingly popular in recent years as a way to lose weight, regulate blood sugar levels, and even improve sleep. But is intermittent fasting really as healthy as it seems? We take a closer look at the different forms of intermittent fasting, the pros and cons, and Insentials' tips for using intermittent fasting in a smart and healthy way.

Intermittent fasting (IF) is an eating pattern that alternates between periods of eating and fasting. The principle has existed since the early 20th century, when it was mainly studied and applied to treat obesity. The idea was to enable the body to burn stored fat through specific periods without food intake. This would aid in weight loss and improve metabolic health (Patterson & Sears, 2017)[1]. IF is unique in that it encourages the body to draw energy from alternative sources during fasting periods. This enhances metabolic flexibility, or the body's ability to switch smoothly between burning sugar and fat. This is crucial for maintaining a healthy energy balance. Research also suggests that IF can not only aid in weight management but may also affect processes such as circadian rhythms and the gut microbiome, impacting overall health (Patterson & Sears, 2017)[1].

Intermittent fasting offers a lot of flexibility and can provide benefits, but each type also has potential drawbacks that depend on personal preferences and health goals. Below, we discuss the most common schedules.

With the 12:12 method, you fast for 12 hours and eat during the remaining 12 hours. This pattern often aligns with the natural eating habits of people and can serve as an accessible introduction to IF. [²]

Pros:

Cons:

In this method, you fast for 16 hours and limit your eating period to 8 hours. For example, you might eat between 12:00 and 20:00 and fast for the rest of the day and night. This method is popular due to its simplicity and the ability to have meals within a shorter timeframe. [³]

Pros:

Cons:

This pattern involves eating normally for five days a week and limiting calorie intake to about 500-600 calories per day on two non-consecutive days. This approach can help with weight management and metabolic health. [⁴]

Pros:

Cons:

In ADF, you alternate between days of normal eating and days of complete fasting or very limited calorie intake. Research suggests that ADF can contribute to weight loss and improved cardiovascular markers. [⁵]

Pros:

Cons:

This method involves a full 24-hour fasting period once or twice a week. While some people find this effective for weight management, it can be challenging to sustain. [⁶]

Pros:

Cons:

With OMAD, you consume all your daily calories in one meal within an hour, followed by 23 hours of fasting. This extreme form of IF requires careful planning to ensure sufficient nutrient intake. [⁷]

Pros:

Cons:

Intermittent fasting (IF) is an eating pattern that has become popular for achieving health benefits such as weight loss and metabolic improvements. Below is an overview of the potential pros and cons of IF, with specific attention to metabolic flexibility. [8], [9].

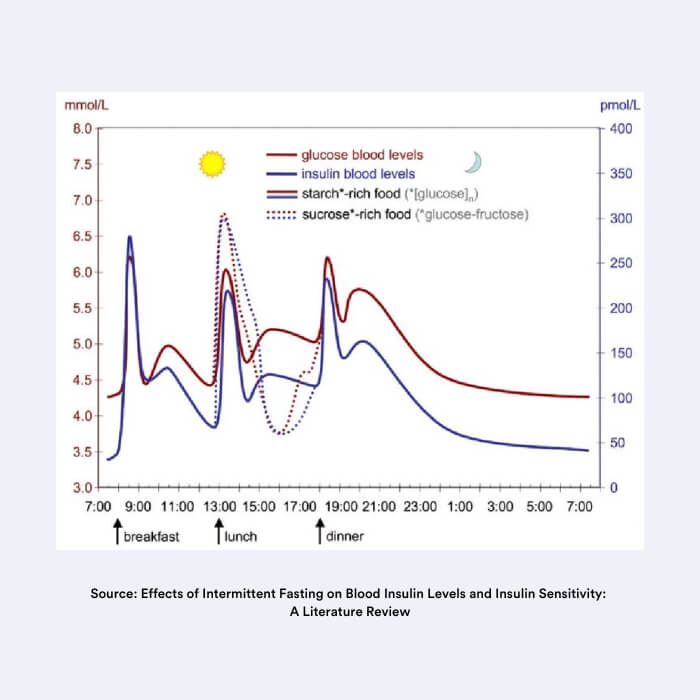

Research shows that IF can help reduce body weight and improve insulin sensitivity. By alternating periods of fasting with eating periods, the body can manage insulin more efficiently, which may reduce blood sugar spikes after meals. A recent study found that IF improved insulin response and reduced body weight. This suggests that IF can be beneficial for managing type 2 diabetes and obesity (de Cabo & Mattson, 2019). [9]

Intermittent fasting encourages the body to switch between burning fat and sugar as energy sources, known as metabolic flexibility. This process is important because, during fasting, the body accesses fat reserves for energy. This promotes weight loss and more efficient energy use. Research indicates that regular fasting periods increase fat burning and support metabolic flexibility. This process was also crucial in prehistoric times for energy management during periods of food scarcity (Cienfuegos et al., 2020) [8].

IF can help reduce risk factors for cardiovascular diseases. Improved insulin sensitivity and reduced body fat can also lead to better blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and triglycerides. These are factors associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular diseases (de Cabo & Mattson, 2019) [9].

Although IF can reduce body fat, it may also lead to muscle loss if sufficient protein intake is not maintained or if resistance training is not practiced. Studies show that muscle loss is possible during longer fasting periods, though this effect can be minimized with careful dietary intake and strength training (Cienfuegos et al., 2020) [8].

IF can affect hormone levels, particularly in women. During longer fasting periods, the body may exhibit a decrease in thyroid and reproductive hormones, which can lead to menstrual irregularities in some women. Men can also experience a reduction in testosterone during extended fasting periods. However, these effects depend on the frequency and duration of fasting (Cienfuegos et al., 2020) [8].

Intermittent fasting can also take a psychological toll, especially for individuals prone to eating disorders. There is an increased risk of developing obsessive thoughts about food or binge eating during eating periods. This can potentially cause stress and impact mental health. Social activities involving food can also become more challenging for those who strictly adhere to their fasting schedule (de Cabo & Mattson, 2019) [9].

Combining intermittent fasting (IF) with physical training can be challenging, particularly when it comes to timing and nutrition type. Various factors need to be considered, such as energy levels, muscle maintenance, and post-workout recovery.

Training in a fasted state, for example, in the morning before the first meal, can stimulate fat burning and improve insulin sensitivity. During fasting, the body needs to tap into its energy reserves, often leading to a higher rate of fat burning. Research shows that exercising during a fasting period can enhance mitochondrial capacity (the energy factories of the cell). This results in increased efficiency in fat burning (Moro et al., 2016) [10].

However, training without prior nutrition can negatively affect performance, especially for intensive workouts like strength training or HIIT (High-Intensity Interval Training). The body may experience a lack of quick energy, which, according to research, can lead to fatigue and a decrease in training performance (Stannard et al., 2010) [11].

The timing of nutrient intake after a workout is crucial for muscle recovery and growth, particularly when combined with IF. Since the body may experience glycogen and amino acid depletion after fasting and training, a diet rich in protein and carbohydrates helps support the recovery process. A study suggests that protein intake after fasted training helps prevent muscle breakdown and promotes protein synthesis, which is important for muscle recovery (Tinsley & La Bounty, 2015) [11].

Consuming carbohydrates immediately after training can help replenish muscle glycogen stores, which can improve performance and energy levels for the next workout session.

For those who feel fatigued during workouts in a fasted state, a small pre-workout meal can help boost energy without losing the benefits of IF. For example, a light, protein-rich snack before training can enhance performance without breaking the fast. Studies recommend planning pre-workout meals carefully, especially for intensive or long workouts (de Souza et al., 2017) [12].

While IF can promote fat loss and insulin sensitivity, there is a risk of muscle loss if not carefully combined with training and sufficient protein intake. Strength training is essential alongside IF to counteract muscle loss, and adequate protein intake can help build muscle mass, even while fasting. Research shows that individuals who follow IF but consume sufficient protein can achieve muscle maintenance and even growth during strength training (Moro et al., 2016) [13].

Hydration plays an important role, especially since fasting can also limit water intake. During intermittent fasting, it is crucial to stay hydrated, particularly around workouts. A lack of hydration can lead to decreased performance and muscle cramps. This applies not only to exercise during intermittent fasting but also to sports in general. So: stay hydrated!

Intermittent fasting affects sleep quality and duration. Research suggests that IF can strengthen the circadian rhythm, leading to improved sleep. Additionally, IF may increase the production of growth hormone, which contributes to better sleep.

A study published in Cell Metabolism [14] examined the effects of time-restricted eating on mice and humans. The results showed that time-restricted eating improved sleep quality and extended sleep duration. This suggests that limiting the eating window can impact the sleep-wake cycle.

However, not all studies agree on the effects of IF on sleep. A study published in The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition [15] found no significant improvement in sleep quality among participants following IF. This highlights the variability of IF's effects on sleep.

Therefore, IF can have positive effects on sleep quality and duration, but the results vary. Individuals may experience different reactions. It is important to consider personal experiences and scientific findings.

During social eating occasions, there can also be pressure to eat, especially when others are not following a fasting regimen. This can lead to internal conflicts or feelings of guilt when someone does not participate in a shared meal. Studies show that this social pressure can make fasting difficult for some people, potentially undermining their motivation (Tinsley & La Bounty, 2015) [17].

On the other hand, there are also benefits to fasting in social contexts. Some people discuss their new eating plan with others, and in some cases, starting a joint plan within a family or friend group can strengthen bonds, as everyone adheres to a similar goal (Sutton et al., 2018) [18].

Various studies suggest that intermittent fasting can help people gain more control over their eating habits. The structured pattern of fasting can lead to a more mindful approach to food and mealtimes. For some, this helps develop a healthier relationship with eating. This can be particularly beneficial for individuals struggling with binge eating or emotional eating (Sutton et al., 2018) [18]. The ability to plan meals and adhere to fasting periods can also enhance feelings of satisfaction and self-control.

On the other hand, the rigid structures of intermittent fasting can increase stress and anxiety, especially in individuals already prone to eating-related issues. In some cases, adhering to a fasting regimen can lead to obsessive thoughts about food or binge eating. This can negatively impact mental well-being. Research has shown that rigidly following a diet, such as IF, can increase stress and eating-related anxiety, particularly when fasting periods are too strict or when fasting is perceived as a burden rather than a choice (Cienfuegos et al., 2021) [19]. It should never be the case that your mental health suffers due to intermittent fasting. Therefore, do not continue fasting at any cost if you find it difficult.

Does intermittent fasting make us smarter? There is evidence that cognitive functions can improve through IF. Some studies indicate that it can increase the production of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). This can contribute to better concentration and a clearer mind. It can be especially useful for people seeking mental clarity or focus, as the brain can function more efficiently during fasting due to fewer blood sugar fluctuations (Tinsley & La Bounty, 2015) [17].

If you're curious about intermittent fasting and want to try it yourself, there are some handy guidelines to help you integrate this method responsibly into your life. Here’s a summary of our own tips.

We get it. You’ve read about the benefits of IF and want to jump right in. It can be tempting to schedule a longer fasting period, like 16 hours, right away. However, if you’re not used to fasting, it’s better to start slowly.

Begin with a shorter fasting period, such as 12:12 (12 hours of fasting and 12 hours of eating), and gradually extend this as your body adapts. Building up step by step helps prevent you from going too fast and ensures that your fasting routine is sustainable.

The internet and social media are full of advice about intermittent fasting, but remember that every body responds differently. What works for one person may not necessarily be right for you. Your own body is the best advisor. If it signals that you are hungry or not feeling well, it’s okay to eat. Stay aware of your body’s signals and adjust your routine accordingly.

Intermittent fasting doesn’t have to be a daily obligation. It’s perfectly possible to take a flexible approach where you adapt your fasting times to your schedule. For instance, you could choose not to fast on weekends so you can enjoy meals with family or friends without worrying about your fasting period. This way, you maintain balance and prevent IF from feeling restrictive.

There’s a common misconception that IF always means skipping breakfast, but this doesn’t have to be the case. You can just as well decide to skip dinner, depending on what suits your lifestyle and energy needs.

Some people find they need more energy in the morning and prefer to skip dinner. Others start their day with a cup of coffee or tea and have their first meal later. The key is to experiment and find what gives you the most energy and satisfaction.

Want to learn more about intermittent fasting and discover how to apply it in a healthy and achievable way? Our experts are ready to help you. Feel free to contact us. We look forward to supporting you on your path to a healthy lifestyle!

Sources:

[1] Patterson, R.E., & Sears, D.D. (2017). Metabolic effects of intermittent fasting. Annual Review of Nutrition, 37, 371-393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064634

[2] Wilkinson, M. J., Manoogian, E. N., Zadourian, A., et al. (2020). Ten-Hour Time-Restricted Eating Reduces Weight, Blood Pressure, and Atherogenic Lipids in Patients With Metabolic Syndrome. Cell Metabolism, 31(1), 92-104.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.11.004

[3] Gabel, K., Hoddy, K. K., Haggerty, N., et al. (2018). Effects of 8-hour time restricted feeding on body weight and metabolic disease risk factors in obese adults: A pilot study. Nutrition and Healthy Aging, 4(4), 345-353. https://doi.org/10.3233/NHA-170036

[4] Harvie, M. N., Pegington, M., Mattson, M. P., et al. (2011). The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. International Journal of Obesity, 35, 714–727. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.171

[5] Bhutani, S., Klempel, M. C., Kroeger, C. M., et al. (2013). Alternate day fasting and endurance exercise combine to reduce body weight and favorably alter plasma lipids in obese humans. Obesity, 21(7), 1370–1379. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.20353

[6] Varady, K. A., & Hellerstein, M. K. (2007). Alternate-day fasting and chronic disease prevention: a review of human and animal trials. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 86(1), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/86.1.7

[7] Tinsley, G. M., & La Bounty, P. M. (2015). Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 661-674. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv041

[8] Cienfuegos, S., Gabel, K., Kalam, F., Lin, S., Oliveira, M. L., Varady, K. A. (2020). Effects of intermittent fasting on health markers in humans and animals. Nutrition Reviews, 78(12), 201-213. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuz079

[9] de Cabo, R., & Mattson, M. P. (2019). Effects of Intermittent Fasting on Health, Aging, and Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(26), 2541-2551. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1905136

[10] Moro, T., Tinsley, G., Bianco, A., & Marcolin, G. (2016). Effects of eight weeks of time-restricted feeding (16/8) on basal metabolism, maximal strength, body composition, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk factors in resistance-trained males. Journal of Translational Medicine, 14, 290. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-016-1044-0

[11] Stannard, S. R., Thompson, M. W., Fairbairn, K. A., Huard, B., Sachdev, P., & Thom, J. (2010). The effect of fasting and carbohydrate prefeeding on skeletal muscle metabolism during exercise in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology, 109(5), 1555–1562. https://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00513.2010

[12] Tinsley, G. M., & La Bounty, P. M. (2015). Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 661-674. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv041

[13] de Souza, R. J., Kendall, C. W., & Jenkins, D. J. (2017). Intermittent fasting: the science of meal timing for health and longevity. Annual Review of Nutrition, 37, 371-393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-071816-064634

[14] Sutton, E. F., Beyl, R., Early, K. H., Cefalu, W. T., & Ravussin, E. (2018). Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even Without Weight Loss in Men With Prediabetes. Cell Metabolism, 27(6), 1212-1221.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010

[15] Cienfuegos, S., Gabel, K., Kalam, F., Ezpeleta, M., & Varady, K. A. (2021). Effects of intermittent fasting on sleep: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(6), 1455-1463. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa421

[16] Hatori, M., Vollmers, C., Zarrinpar, A., Ditmer, K., & Panda, S. (2012). Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metabolism, 15(6), 848-860. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2012.04.019

[17] Tinsley, G. M., & La Bounty, P. M. (2015). Effects of intermittent fasting on body composition and clinical health markers in humans. Nutrition Reviews, 73(10), 661-674. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuv041

[18] Sutton, E. F., Beyl, R., Early, K. H., Cefalu, W. T., & Ravussin, E. (2018). Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even Without Weight Loss in Men With Prediabetes. Cell Metabolism, 27(6), 1212-1221.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.04.010

[19] Cienfuegos, S., Gabel, K., Kalam, F., Ezpeleta, M., & Varady, K. A. (2021). Effects of intermittent fasting on sleep: A systematic review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 113(6), 1455-1463. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa421

The social and psychological impact of intermittent fasting

Intermittent fasting can affect not only physical health but also social and psychological aspects of life. The way people adapt to IF eating patterns, and the influence on social interactions and mental health, can vary greatly. Research on the psychological and social effects of IF presents a mixed picture.

The social impact of intermittent fasting

Limitations in social situations

One of the main social challenges of intermittent fasting is its impact on social eating occasions. Eating is often a social bonding activity. Fasting periods can make it difficult to participate in meals, leading to feelings of discomfort, especially during family or friends' gatherings where food plays a central role. People following IF may find themselves compelled to skip meals or feel uneasy eating in company, which can affect the social experience (Hatori et al., 2012) [16].